U.S. – China

Trade Agreements; Will a New Administration Have Better Luck?

By the Curmudgeon

Introduction:

In July 2020 we wrote about last January’s highly touted U.S. - China trade deal and

reported that the results had been quite disappointing. We now conclude the deal was an outright

failure, primarily because of China’s non-compliance.

Let’s first

examine the origins of the trade war, the terms of the trade pact and an

assessment of its success or failure.

The expiration of exclusions for China tariffs as well as President

elect Biden’s position on same are detailed. The NYSE delisting of China state

owned telecommunications companies and the way they’re

controlled by China’s Communist Party is also described.

Finally, conclusions from the

Brookings Institute are presented along with the Curmudgeon’s main gripe about

the deteriorating U.S. - China trade relationship.

Origins of the U.S. - China

Trade War:

President Trump launched the

U.S. - China trade war to pressure Beijing to implement significant changes to

aspects of its economic system that facilitate unfair Chinese trade practices,

including forced technology transfer, limited market access, intellectual

property theft, and subsidies to state-owned enterprises. Trump argued that

unilateral tariffs would shrink the U.S. trade deficit with China and cause

multi-national companies to bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States.

Between July 2018 and August

2019, the U.S. announced plans to impose tariffs on more than $550 billion of

Chinese products, and China retaliated with tariffs on more than $185 billion

of U.S. goods.

A September 2019 study by Moody’s

Analytics found that the trade war had already cost the U.S. economy nearly

300,000 jobs and an estimated 0.3% of real GDP. Other studies put the cost to

U.S. GDP at about 0.7%. A 2019 report from Bloomberg Economics estimated that

the trade war would cost the U.S. economy $316 billion by the end of 2020,

while more recent research from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and

Columbia University found that U.S. companies lost at least $1.7 trillion in

the price of their stocks as a result of U.S. tariffs

imposed on imports from China.

Capsule Summary of Trade Deal:

Signed with great fanfare in

January 2020, the “Economic and Trade Agreement Between the United States of

America and the People’s Republic of China: Phase One” went into effect on

February 14, 2020.

The U.S.-China trade agreement

called for China to purchase a combined $200 billion of certain U.S. goods and

services over 2020 and 2021 from 2017 levels. China committed to purchase no

less than an additional $63.9 billion of covered goods from the United States

by the end of 2020 relative to the 2017 baseline. Defining the 2017 baseline

using US export statistics implies a 2020 target of $159 billion. Nothing in the text of the agreement

indicates China must meet anything other than the year-end targets. Also, the U.S. tariffs placed on

certain imported goods from China were not reduced or removed by the trade pact

(more below).

A complete implementation of

the trade deal was intended to help both countries while paving the way for

Phase 2 talks on other key issues such as subsidies, cybersecurity and digital

trade, officials said at the time.

“Amid increasing bilateral

tensions across the relationship, working together to improve trade and grow

commerce can provide important benefits to both economies and help to improve

relations,” they wrote in the letter.

Missing from the trade deal

was any forward movement on subsidies, state-owned enterprises, and China’s

uses of industrial policy to advantage its own firms over foreign competitors.

Those topics were to be addressed in Phase 2 of the deal, which is now on hold

pending actions of the Biden administration (see subheading below).

Tracking the Trade Pact:

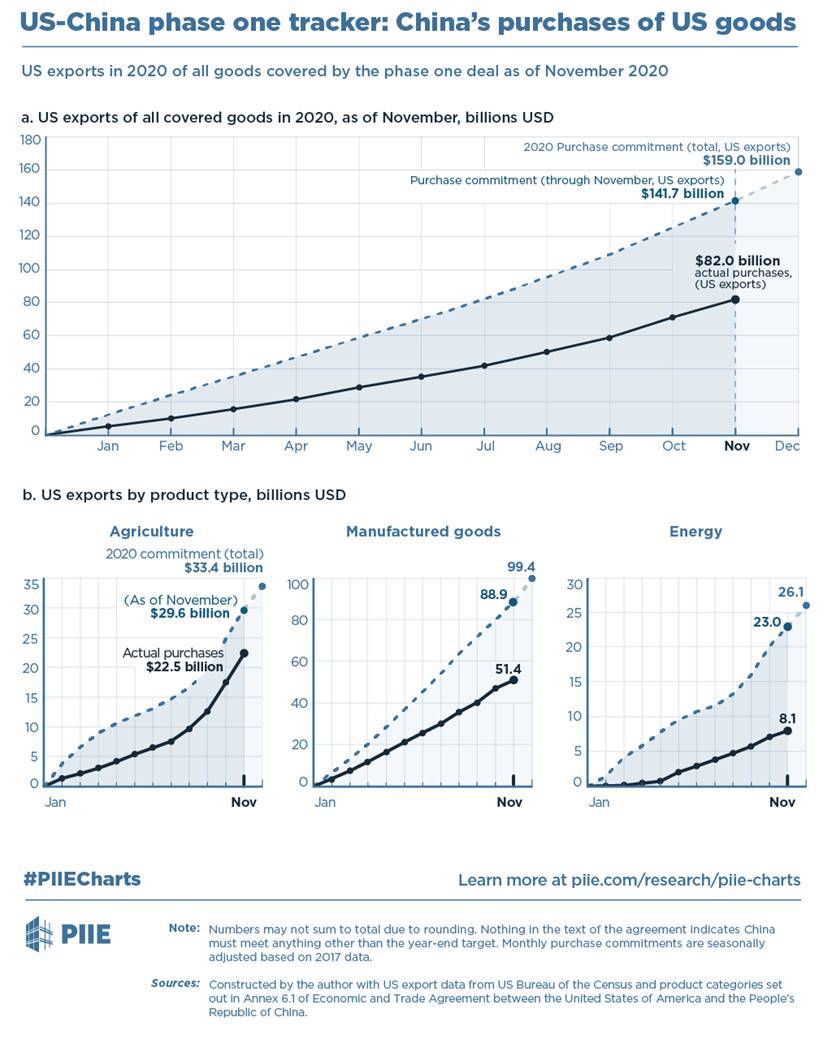

The Peterson Institute of

International Economics (PIIE) notes that through November 2020,

U.S. exports to China of products covered by the trade pact were $82.0 billion,

compared with a year-to-date target of $141.7 billion. Through the first eleven

months of 2020, China's purchases of all covered products were thus only at 58%

of their year-to-date targets.

The charts below track China’s

monthly purchases of U.S. goods covered by the deal, relying on data from the U.S.

Census Bureau (for U.S. exports). It then compares those purchases with the

legal agreement’s annual targets, prorated on a monthly basis

based on seasonal adjustments, above a baseline scenario.

Tariff Exclusions on China

Exports to the U.S. Have Expired!

The U.S. began placing tariffs

on more than $360 billion of Chinese goods in 2018. Those tariffs were not covered by the U.S. -

China Phase 1 trade deal.

Numerous studies have found

that U.S. companies primarily paid for those tariffs. They have cost U.S. importers $71.6

billion since they started in July of 2018, according to U.S. Customs data.

The tariffs forced American

companies to accept lower profit margins, cut wages and jobs for U.S. workers,

defer potential wage hikes or expansions, and raise prices for American

consumers or companies. They forced companies to tear up supply chains, roiled

financial markets and slowed economic growth well before the coronavirus

pandemic hit.

A spokesperson for the American

Farm Bureau stated that “farmers have lost the vast majority of what was

once a $24 billion market in China” as a result of

Chinese retaliatory actions.

Meanwhile, thousands of

companies asked the Trump administration for temporary waivers excluding

them from the tariffs. Companies that met certain requirements were

exempted from paying the levies, which range from 7.5% to 25%. Those included

firms that import electric motors, microscopes, salad spinners, thermostats,

breast pumps, ball bearings, forklifts and other

products.

The bulk of the tariff

exclusions, which could amount to billions in revenue for businesses based

in the U.S., expired on January 1st (this past Friday). As a

result, many companies now have to again pay a tax to

the U.S. government to import a variety of goods from China, including

textiles, industrial components and other assorted products.

Some companies say the tariff

exclusions process was very unfair. While large companies have invested huge

sums in hiring Washington DC law firms to lobby the administration and apply

for exemptions, some small companies lacked the resources to apply for and win

exclusions.

“Allowing these exclusions to

expire — especially because the facts supporting their original determination

remain unchanged — shows how arbitrary and capricious this process has been,”

said Stephen Lamar, the chief executive of the American Apparel & Footwear

Association, which represents makers of shoes and clothing. “These companies could ill afford a tax on

their imported inputs and U.S. workers when they originally applied for these

exclusions and they certainly can’t afford one now,” he added.

Biden Administration Position

on Trade Deal and China Tariffs:

“Trump’s ‘phase one’ trade deal with China is failing -

badly,” Joe Biden said in an August 5th statement to Reuters. Biden added that the current trade deal is

“unenforceable,” and “full of vague, weak, and recycled commitments from

Beijing,” allowing the country to keep “providing harmful subsidies to its

state-owned enterprises” and “stealing America’s ideas”.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer told

Reuters on December 16th that Biden should keep

pressing China to stick to the “Phase 1” trade deal and use tariffs as

leverage. “I would hold their feet to

the fire on Phase 1. I think in some

parts they (China) have done a reasonably good job, in other parts they

haven’t,” Lighthizer said.

On December 28th Stratfor wrote that

“the Biden administration will probably maintain many of the existing U.S.

tariffs on China, ushering in a lengthy period of restrictions that will likely

prompt businesses to consider shifting their supply chains and operations

outside China.”

In an interview in December

with The New York Times, Biden said that he

would conduct a full review of the United States’ trade relationship with China

and consult with allies in Asia and Europe to develop a coherent strategy

before making changes. “I’m not going to

make any immediate moves, and the same applies to the tariffs,” Biden said.

PHOTO CREDIT: REUTERS/ALY SONG

Does this photo accurately depict economic harmony

between China and the U.S.?

……………………………………………………......………….………………………..

Recent Example of Increased U.S. - China Economic

Tension:

On December 31st, the New York Stock Exchange

(NYSE) said it will delist China’s three large state owned telecom carriers. China Mobile, which is among the most valuable of China’s listed

state-owned enterprises, will be removed from the Big Board along with China

Unicom and China Telecom. The move was expected after a November U.S.

government order barring Americans from investing in companies that help the

Chinese military.

In May, the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

barred China Mobile from operating in the U.S. In December, it ordered

carriers to remove equipment made by Huawei Technologies, and started

looking into whether China Telecom should be allowed to operate in

America.

All three telecoms companies (telcos)

operate under Beijing’s firm control. They are ultimately owned by a government

agency, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission,

and are often ordered to pursue Beijing’s goals. China’s ruling Communist Party

(CCP) sometimes moves executives from one of those telcos

to another. They are the only three

companies in China that are permitted to provide broad telecommunications

network services, which Beijing regards as a strategic industry that must

remain under state control.

Xi Jinping, China’s top leader

(President of the People’s Republic of China 中华人民共和国主席), has talked about making state companies bigger and stronger rather than

more streamlined. That has led to concerns among some economists and

entrepreneurs that the Chinese government is taking a greater role in private

enterprise.

Conclusions:

The Brookings Institute writes that “the ultimate results of the Phase 1 trade deal between China and the

United States — and the trade war that preceded it — have significantly hurt

the American economy without solving the underlying economic concerns that the

trade war was meant to resolve. Progress on market access also proved

underwhelming outside of the financial sector.”

And as noted above, China's purchases of all covered products were only

at 58% of their year-to-date targets with only one month remaining in

2020.

Victor concurs that the trade

deal was not a success but adds that the Trump administration deserves credit

for trying to end the trade war and improve economic relations with China. The Curmudgeon

believes that the biggest failure of the deal was its inability to make

significant progress in fundamentally resolving the structural imbalances of

the U.S.-China trade relationship.

Forced technology transfer is a particular concern. To gain

access to the Chinese market, American companies (e.g., Qualcomm, HPE, Intel,

AMD, etc.) have been forced to transfer technology to Chinese entities, create

joint ventures, lower prices, and aid homegrown China players. Those efforts

form the backbone of President Xi Jinping’s ambitious plan to ensure that

China’s companies, military, and government dominate core areas of

technology like artificial intelligence, telecommunications equipment, and

semiconductors.

Other critical issues not resolved by the trade

pact include limited market access/China government protected domestic markets

(across the board), intellectual property theft (e.g., Huawei), and subsidies

to state-owned enterprises (e.g., China Unicom, China Mobile, China Telecom as

per the above discussion).

Closing Quotes:

“There’s a great deal of unease in Washington. The

defense, intelligence agencies and others are concerned that advanced

chip-making capabilities are going to China,” said James Lewis, an analyst at

the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based

think tank.

“If it’s really based on the genuine commitments that they

inked in January, China is far behind and they’re never gonna

catch up,” Scott Kennedy, senior advisor and Trustee Chair in Chinese Business

and Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies told CNBC’s Squawk Box Asia.

“This China trade deal is basically like the Bobby Knight

(x-Indiana basketball coach) of trade deals. You know, you abuse, you abuse,

you abuse, and then they say ‘Well, OK, we’ll let you try one more time.’” David E. Bonior

………………………………………………………………………………………….

Good health, stay calm and safe, persevere under

lockdowns and till next time….

The Curmudgeon

ajwdct@gmail.com

Follow

the Curmudgeon on Twitter @ajwdct247

Curmudgeon is a retired investment professional. He has

been involved in financial markets since 1968 (yes, he cut his teeth on the

1968-1974 bear market), became an SEC Registered Investment Advisor in 1995,

and received the Chartered Financial Analyst designation from AIMR (now CFA

Institute) in 1996. He managed hedged equity and alternative

(non-correlated) investment accounts for clients from 1992-2005.

Victor

Sperandeo is a historian, economist and financial innovator who

has re-invented himself and the companies he's owned

(since 1971) to profit in the ever changing and arcane world of markets,

economies and government policies.

Victor started his Wall Street career in 1966 and began trading for a

living in 1968. As President and CEO of Alpha Financial Technologies LLC,

Sperandeo oversees the firm's research and development platform, which is used

to create innovative solutions for different futures markets, risk parameters

and other factors.

Copyright © 2021 by the Curmudgeon and

Marc Sexton. All rights reserved.

Readers are PROHIBITED from

duplicating, copying, or reproducing article(s) written

by The Curmudgeon and Victor Sperandeo without providing the URL of the original

posted article(s).