Whatever

Happened to the Inflation Premium on 30-year U.S. Treasury Bonds?

By the

Curmudgeon

Overview:

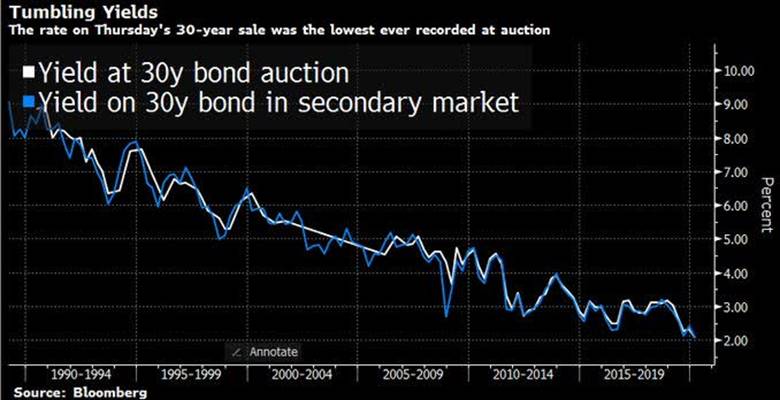

Last Thursday, the U.S.

Treasury sold $19 billion of 30-year

T-bonds [1.] at a 2.06% yield.

That was below the previous record low yield of 2.170% set last October,

according to data from BMO Capital Markets.

On Friday, the 30-year T-bond yield closed at 2.04% and was trading at

2.02% on Monday afternoon when this article was written.

Meanwhile, the Consumer

Price Index (CPI) for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 2.5 percent

over the last 12 months to an index level of 257.971 (1982-84=100). For the

month, the index increased 0.4 percent prior to seasonal adjustment.

Combining those two data points and you get a negative real

yield of -0.46% (-46 bps) on the 30-year T-bond, based on Fridays close. To the best of my knowledge that has never

happened before, yet no journalist has called attention to it.

Note 1. In 1974, 25-year T-bond

issues became a regular feature of Treasurys mid-quarter coupon refunding. In 1977,

30-year T-bond issues replaced the 25-year T-bond issues.

..

Defining the Inflation

Premium:

Ever since 25 or 30-year T-bonds were auctioned, there was an

inflation premium [2.] of three to five percent (depending

on the direction of inflation and bond market volatility) built into the

nominal yield.

Note 2. The inflation

premium can be estimated as the difference between the Treasury bond yield MINUS

the yield of Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) of the same

maturity. Inflation Premium = YieldTB YieldIP

Where YieldTB is the yield on a Treasury bond

and YieldIP is the yield

on Treasury

inflation-protected security of the same coupon rate, redemption

value, maturity, etc.

If we already have a nominal

rate and a real rate, we can isolate inflation risk premium using the following

equation:

|

Inflation

Premium = |

1

+ Nominal Rate |

− 1 |

|

1

+ Real Rate |

There is also a maturity

premium (e.g. the difference between the 30-year Treasury and the 10-year

Treasury yields). Because the interest

rate risk is greater for the 30-year Treasury, investors demand a maturity

premium over a shorter duration bond to compensate for that risk. Lately, the maturity premium has been

shrinking as the 30-year T-bond yield has dropped faster than the 10-year

T-note yield.

Now it seems the demand for U.S. long bonds is so voracious

that buyers dont mind losing purchasing power by holding a long T-bond for 30

years. Alternatively, the bond market

may be forecasting zero inflation (or deflation) for the next 30 years. Or

T-bond traders are expecting even lower yields so they can sell bonds purchased

today at a profit tomorrow?

I expect the Treasury 10-year yield to fall to zero, perhaps

within two years, said Akira Takei, a global fixed-income fund manager at

Asset Management One Co., which oversees more than $450 billion. Ive been

overweight U.S. Treasuries. Thats based on my view that developed economies

are facing a combination of aging demographics and falling birth rates, slow

growth and low inflation.

Where is the Demand for

Long T-Bonds Coming From?

·

Pension funds have been

ramping up bond allocations for more than a decade after a change in regulations. They now hold a record amount

of longer-dated Treasuries.

·

Bond mutual funds saw a

historic inflow of money last year, with no sign of a slowdown. In the week

ending February 12th, Taxable Bond Fund Inflows were $11.7 Billion.

·

Banks are buying record amounts

of Treasuries [3.] as they scale

back their lending. For example

..

·

The Financial Times reported in November that JP Morgan Chase had bought more than $130 billion of long-dated bonds and cut the amount of loans it holds, marking a major shift in how the

largest U.S. bank by assets manages its enormous balance sheet. The twin moves, which have seen the banks

bond portfolio increase by 50 per cent, are prompted by capital rules that

treat loans as riskier than bonds. JP Morgans new approach comes down to an

economic decision: they can make more money selling [loans] than buying them. Its incredible, said an executive at a

large institutional investor. The scale of what JPMorgan is doing is mind-boggling . . . migrating out of cash

into securities while loans are flat to down.

Note 3. On August

29, 2018, Zero Hedge reported:

banks arent required

to mark government securities to market for accounting purposes. Throw in the

zero risk-weighting for government securities in required capital calculations,

and in theory, banks can infinitely buy government bonds and still not have to

put up additional capital.

In other words, heavily

skewed regulations have gifted banks the proverbial money machine. And by

cranking that machine, the banking sector has become a gigantic and somewhat

price-insensitive government bond buyer, one on which the Treasury Department

can depend even as debt spirals higher.

Victor

had first noted these new rules for banks in this article, which was

subsequently republished at Zero Hedge.

This is the part I liked best:

The really

interesting part is skirting around mark-to-market accounting. Since the

banking crisis, banks have been permitted to hold assets in a special account

called an HTM (held to maturity) account. Government debt held in this account is not

marked to the market.

So even if interest rates rise and the prices of the bonds

fall, the bank reports no decline in the value of the debt, which means no

negative effect on quarterly earnings. But it still gets to collect the interest.

·

While the Fed continues to buy T-bills at a rapid

clip (see last weeks post: Curmudgeon:

Fed T-Bill Buying Persists Despite Ultra Easy Financial Conditions),

it is not buying long term Treasuries at this time.

·

China has steadily accumulated

U.S. Treasury securities over the last few decades. As of May 2019, China owned

$1.11 trillion, or about 5%, of the $22 trillion U.S. national debt, which is

more than any other foreign country.

Buy the Dip Mentality

Extends to Treasuries:

With U.S. long term treasuries at or near all-time lows,

buyers are still buyers ready to pounce and buy every dip (see chart

below). Even surging stocks, record

auction sizes and the tightest labor market since the 1960s can barely make a

dent in bond prices.

A Global Fixed Income Perspective:

Investors apparently hunger for ANY positive nominal yield

in a global market with nearly $14 trillion of negative-yielding debt. It could

also be a sign that some investors are hesitant to take on additional risk

until they know more about the potential spread of coronavirus.

The demand for (Thursdays 30-year T-Bond) auction was

amazing considering the low coupon, Simons and McCarthy wrote in a Thursday

note. However, yield is hard to find around the world.

The appetite for debt has extended to sovereign obligations

of all flavors. One example: Greek 10-year rates once near 45% slid below 1%

this month. The countrys junk rating is proving little deterrent with the

worlds pile of negative-yield debt climbing above $13 trillion amid the latest

global bond rally.

Closing Quote:

Low yields may well be a sign that bond markets are

correctly priced for the likely risks posed by the virus outbreak, wrote

Gaurav Saroliya, director of macro strategy with

Oxford Economics.

.

Good luck and till next time

.

The Curmudgeon

ajwdct@gmail.com

Follow

the Curmudgeon on Twitter @ajwdct247

Curmudgeon is a retired investment professional. He has

been involved in financial markets since 1968 (yes, he cut his teeth on the

1968-1974 bear market), became an SEC Registered Investment Advisor in 1995,

and received the Chartered Financial Analyst designation from AIMR (now CFA

Institute) in 1996. He managed hedged equity and alternative

(non-correlated) investment accounts for clients from 1992-2005.

Victor

Sperandeo is a historian, economist and financial innovator who

has re-invented himself and the companies he's owned (since 1971) to profit in

the ever changing and arcane world of markets, economies and government

policies. Victor started his Wall Street

career in 1966 and began trading for a living in 1968. As President and CEO of

Alpha Financial Technologies LLC, Sperandeo oversees the firm's research and

development platform, which is used to create innovative solutions for

different futures markets, risk parameters and other factors.

Copyright © 2020 by the Curmudgeon and

Marc Sexton. All rights reserved.

Readers are PROHIBITED from

duplicating, copying, or reproducing article(s) written

by The Curmudgeon and Victor Sperandeo without providing the URL of the

original posted article(s).