Another Stock Market Myth

Debunked—Earnings Don’t Drive Stock Prices!

By The Curmudgeon

In last week's Curmudgeon article we forecast that

U.S. GDP growth would not top 2% and that corporate profits would not increase

significantly next year, even if the fiscal cliff were to be avoided. We left

it to the reader to determine how that might affect stock prices, with the

assumption that the GDP growth rate influenced corporate profits which in turn

drove stock prices. Growth in profits along with expected return from

alternative asset classes, especially fixed income, are commonly thought to be

the main drivers of equity prices.

But recent studies show that corporate profits really don't

have a significant effect on stock prices- at least not during any period less

than an entire decade (or longer)!

Take this past year as an example. The domestic economy has

grown at an annual pace only slightly above 2%, quite subpar by historical

average of 3.5%. Overseas, the picture is worse: Japan is teetering on the

brink of yet another recession, Europe is burdened with a sovereign debt crisis

and the Euro-zone's economies are contracting (Greece and Spain are in a

depression). China’s growth has slowed markedly; raising concerns about global

growth in the future. Yet against this bleak backdrop, United States stocks, as

measured by the S&P 500 have returned 15 percent this year. Stocks traded

in Europe have gained 18 percent and Asian stocks are up more than 12 percent

(more if Japan is excluded).

That seems like a huge disconnect, but only if you believe

that earnings drive stock prices. Let's look at a few studies that show that's

not the case.

1. Gerstein Fisher

of Real Life Finance analyzed the historical relationship between GDP

growth and stock price performance in eight major developed and developing

countries between January 1, 1993 and December 31, 2010 (see charts in this article).

Fisher found that the correlation

between annual stock returns and economic growth is very tenuous– typically

quite low and often even negative. There was a huge discrepancy in terms of the

ratio of compounded stock returns to compounded GDP growth. For example,

China’s booming economy expanded by 15.75% annualized (in nominal, US-dollar

terms), yet its stocks actually declined by 2.25% per year over the 18-year

period we looked at. Brazil stocks returned a sizzling 16.11% atop a much lower

compounded economic growth rate of 9.76%. The US had a comparatively modest

economic growth rate of 4.79% but a very respectable annualized stock return of

8.14%, or 70% higher than the underlying economic growth rate.

2. Roger Aliaga-Díaz,

senior economist at the Vanguard Group recently studied returns on equities

going back to 1926, looking specifically at the predictive power of important

variables. Those include market price-to-earnings ratios, growth in gross

domestic product and corporate profits, consensus forecasts for GDP and

earnings growth, past stock market returns, dividend yields, interest rates on

10-year Treasury securities, and government debt as a percentage of GDP.

Their conclusion was that none of these

factors came even remotely close to accurately forecasting how stocks would

perform in the coming year. "One-year forecasts of the market are

practically meaningless," Mr. Aliaga-Díaz says.

Even over a 10-year time horizon, considered by many investors to be long term,

only P/E ratios had a meaningful predictive quality. Over an entire decade,

economic fundamentals like G.D.P. and corporate earnings growth had even less

predictive power over future returns.

Since 1926, those ratios, based on 10

years of averaged earnings — a gauge popularized by the Yale economist Robert

J. Shiller — explained roughly 43 percent of stocks’

performance over the following decade. Of course, "that means about 55

percent of the ups and downs in the market can’t be explained by

valuations," Mr. Aliaga-Díaz says.

For more information, please see:

3. Longtime colleague Mike Dever of Brandywine

Asset Management writes that the apparent intrinsic return from investing

in U.S. stocks over the past 100+ years was really just the result of two

primary factors:

- The aggregate profit (or earnings) growth of the companies that

comprise the market.

- The multiple that people were willing to pay for those earnings (i.e.

the Price/Earnings or P/E ratio)

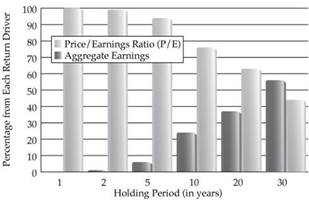

The graph above shows that in any period

of less than ten years, earnings accounted for less than 25% of the

price change in the S&P 500 Total Return index, while changes in the P/E

ratio accounted for more than 75% of this price change. It is only over the

longest periods of time that earnings become the dominant return driver for

equities.

As the graph shows, sentiment

dominates short-term stock performance. Stock prices are driven more by the

psychology of people (or financial institutions) buying and selling stocks than

by corporate earnings. Over the short term, stock prices are driven far more by

(institutional) demand or "market mood" than by realized corporate

earnings.

For more on this, please see:

http://seekingalpha.com/article/496741-what-drives-stock-market-performance

Conclusions:

With more and more of the volume on various stock exchanges dominated

by hedge funds, HFT firms and various other financial institutions, their

collective sentiment (or short term market mood) has become the primary factor

that determines stock prices in the short and intermediate term. With seemingly

inexplicable short term up and down moves, increased correlation between

individual stocks and asset classes, the equity market has become more and more

of a "crap shoot" or casino for individual investors. Recognizing

that reality, individual investors have substantially cut back on their stock

and equity mutual fund ownership over the last several years.

Apparently, it is more important to ascertain the mood of the

market than any other variable or potential determinate of stock prices. And

that market mood or collective sentiment can turn on a dime, with no trigger,

catalyst or logical explanation. Once again, caveat emptor.

Till next time,

The Curmudgeon

Curmudgeon is a retired investment professional. He has been involved in financial markets since 1968 (yes, he cut his teeth on the 1968-1974 bear market), became an SEC Registered Investment Advisor in 1995, and received the Chartered Financial Analyst designation from AIMR (now CFA Institute) in 1996. He managed hedged equity and alternative (non-correlated) investment accounts for clients from 1992-2005.